Religious art has evolved over the centuries, ever since the first crude depictions of martyrdom were etched and drawn in catacombs. At some point symbolism and artistic license became more common in religious art, which leaves us with some rather burning questions.

Did St. Justina have a pet unicorn?

In this rather somber yet fanciful piece of artwork painted in the 1500s, the title tells us that the female saint is “St. Justina.” The artist, however, failed to clue us into which St. Justina. There are actually two: St. Justina of Antioch and St. Justina of Padua.

The unicorn, according to A Handbook of Symbols in Christian Art by Gertrude Sill, is a wild animal that will become tame in the presence of a virgin. So the artist was implying Justina’s virtue and virginity in this image. Both Justina of Antioch and Justina of Padua were virgin martyrs, so the unicorn is not a clue to the identity of the lovely young woman depicted here. What is clear is that neither St. Justina had a pet unicorn, but they did both have courage and virtue enough to die for love of their heavenly spouse, Jesus. (As a side note, the gentleman kneeling in this artwork is thought to be the donor who commissioned the piece.)

Where is this saint’s skin?

In this macabre masterpiece, sculptor Marco d’Agrate depicts St. Bartholomew the apostle. St. Bartholomew was a martyr, like every apostle except John the beloved. In his post-Ascension travels, St. Bart really got around and he was unafraid to stir things up a bit, as he did in Ethiopia and India when confronting idolatry and paganism.

However, after converting the king of Armenia’s brother, things got a bit rough for our sinewy saint. (See what I did there?) He was condemned to death by flaying: having all of his skin removed while still alive. If that isn’t enough to make your skin crawl, now St. Bartholomew is usually depicted in art holding his own skin, to remind us all of how much the saint was willing to suffer for love of God. May we all have that kind of love for our faith as well!

Why are these saints holding their heads?

Every year as Halloween approaches, headless saints get a bit of a popularity boost. Nowhere else can you find a such a legitimate combination of creepy but holy, and also kind of cool for those who want to dress up like saints but want to be a bit edgy about it. Usually St. Denis of Paris is the go-to saint known for head-carrying, because he carried his severed head six miles, preaching the whole time! St. Justus is another headless saint often showcased in art and who asked to have his still talking head brought to his mother so she could kiss it.

Did you know that there are actually many more “headless saints” who didn’t immediately die upon decapitation and they even have a special name? “Cephalophores,” literally translated from greek as “head carriers,” are, true to their etymology, usually depicted in art holding or toting their noggins around. There are apparently around 120 headless saints who continued about their business for a while after their heads were separated from their bodies, inspiring artwork that could certainly turn a few (attached) heads!

Did St. Margaret have a dragon problem?

St. Margaret of Antioch is often pictured with a dragon. No, she didn’t tame it, in fact, the dragon is sometimes depicted as being dead, or with St. Margaret emerging from its belly. (St. Margaret is called Marina in the Greek Churches.) According to the traditional story of her actual martyrdom, St. Margaret was put into prison for refusing to forsake her virginity at the demands of a lustful and selfish Roman prefect. While in prison it is said that the devil came to her in the form of a dragon and devoured her. Margaret, in the belly of the dragon, prayed, and her prayers were no match for the devil, so she busted out of his stomach.

This “rebirth by dragon cesarean” earned St. Margaret a special patronage for pregnant women. Her actual martyrdom is no less dramatic. She was first placed in fire to burn, but was unharmed. Next she was tied up and thrown into a vat of boiling water, but stood up unshackled and unharmed, so she was eventually beheaded. Unlike the cephalophore saints, her beheading was the crown of her martyrdom and she was united with her true love, and Savior in heaven.

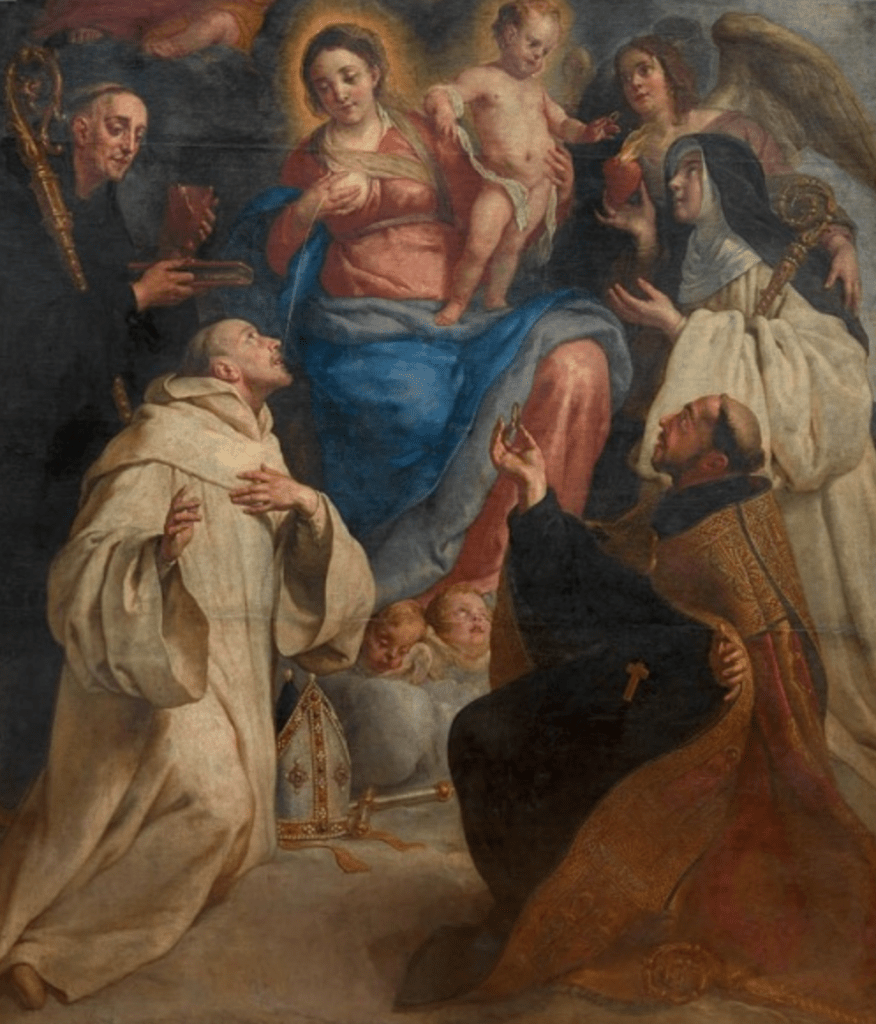

Is Mary really squirting milk at St. Bernard?

“The Lactation of St. Bernard” has been captured by many artists throughout the centuries, particularly by Renaissance artists, who painted during a time when breastfeeding was so culturally accepted that seeing the Blessed Mother nursing or lactating would not have provoked a second glance. The account of the events that inspired this art vary slightly. They center around St. Bernard who, in some stories was said to have mouth sores or an illness that involved his lips, and in others, was praying for Mary to show him how she was truly his Mother. In either case, he then experienced a vision of the Blessed Mother holding the infant Jesus. During this vision Our Lady exposed one of her breasts and squirt milk into the mouth of the saint. From that day on, he was a gifted orator and his difficulties with his mouth were cured. No doubt her heavenly motherhood was proven to the saint beyond a doubt as well!

What other curious or strange artwork have you seen depicting various saints? Do you have a favorite? Tell us in the comments!

Featured Image: Wikimedia commons.

Comments